The Criterion Collection, a continuing series of important classic and contemporary films presents The Hourglass Sanatorium.

Wojciech Jerzy Has’s The Hourglass Sanatorium is a phantasmagorical journey through Polish history and the vanishing Jewish culture of Eastern Europe compliments of the Polish Film School’s most eccentric filmmaker. Józef (Jan Nowicki) travels to a dilapidated hospital where time can be reversed, allowing his dying father to remain in a state where his recovery is once again a possibility. Left to explore the sanatorium on his own, Józef traverses a dream-like voyage through surreal episodes connected to his childhood in search of transcendent knowledge and personal meaning. Rejected by authorities as critical of contemporary Poland, evoking images of the Holocaust during a period of anti-Semitic sentiment in the country, and smuggled into the 1973 Cannes Film Festival where it won the Jury Prize, The Hourglass Sanatorium is a bravely hallucinatory mosaic of history, fantasy, and politics conjured from a dozen stories by the “Polish Kafka,” Galician writer Bruno Schulz.

Wojciech Jerzy Has’s The Hourglass Sanatorium is a phantasmagorical journey through Polish history and the vanishing Jewish culture of Eastern Europe compliments of the Polish Film School’s most eccentric filmmaker. Józef (Jan Nowicki) travels to a dilapidated hospital where time can be reversed, allowing his dying father to remain in a state where his recovery is once again a possibility. Left to explore the sanatorium on his own, Józef traverses a dream-like voyage through surreal episodes connected to his childhood in search of transcendent knowledge and personal meaning. Rejected by authorities as critical of contemporary Poland, evoking images of the Holocaust during a period of anti-Semitic sentiment in the country, and smuggled into the 1973 Cannes Film Festival where it won the Jury Prize, The Hourglass Sanatorium is a bravely hallucinatory mosaic of history, fantasy, and politics conjured from a dozen stories by the “Polish Kafka,” Galician writer Bruno Schulz.

Disc Features:

- New digital restoration, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray

- New introduction by filmmaker Martin Scorsese

- Visual essay by Holocaust scholar Leonard Orr

- New interview with film director Borys Lankosz on his mentor Wojciech Jerzy Has

- PLUS: A booklet featuring a new essay by film critic Rowena Santos Aquino

With Martin Scorsese currently touring his “Masterpieces of Polish Cinema” series, presenting 21 brilliant Polish films in digitally restored masters, now seemed a fitting time for MMC! to finally approach this bounty of great material and, naturally, we’ve chosen one of Poland’s most fabled imaginers – Wojciech Jerzy Has. North American audiences are probably most familiar with Has by way of the now out of print DVD of Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (1965), presented compliments of Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia. UK film fans may know both The Saragossa Manuscript and The Hourglass Sanatorium by way the bare-bones DVD editions released by the Mr Bongo label. Has made a number of other films that are virtually unseen outside of Poland although reports still cite The Saragossa Manuscript and The Hourglass Sanatorium as his masterpieces (hence their inclusion in Scorsese’s program as the only 2 selections from Has). Given that the latter is less known than the former, we’ve selected The Hourglass Sanatorium for our initial foray into the filmography of Wojciech Jerzy Has, although The Saragossa Manuscript is certainly deserving of a re-release by the Criterion Collection.

The titular hourglass carries a double meaning in Polish, referring to both the timepiece and to an obituary notice. Death and remembrance are certainly at the fore in Has’s film. It opens with Józef traveling aboard a spectral train to a ruined hospital where his dying father lays in a state of undeath thanks to the sanatorium’s technique of winding back time and allowing the patient to return to a state when recovery is once again possible. Encouraged by his father’s doctor to rest, Józef is left alone and explores the hospital and its grounds, thereby embarking on a voyage through his own memories and dreams. The Hourglass Sanatorium quickly becomes a phantasmagoria of strange, otherworldly episodes where Józef returns to half remembered memories of his youth made surreal and fantastic. He easily and frequently slips between these moments, his semi-lucid dream journey full of loaded and unpredictable contexts. At times, Józef returns to his childhood friend, the stamp-collecting Rudolph, and a fantasy involving an unattainable girl named Bianca. Other times, he meets with Adela, his town’s local sex idol and a figure of fascination to Józef. Often Józef seeks out and meets with his father, in bird markets, fabric shops, and in his father’s attic sanctuary, usually seeking insight into life and an unusual catalogue Józef asserts is some kind of “authentic book.” Gradually, Józef’s illusions of meaning and knowledge are dispelled and he begins to lose his eyesight, becoming dressed in the garb of the foreboding train conductor depicted at the start of The Hourglass Sanatorium. The film suggests that it is in fact Józef who is dying, held in stasis within his dreams and memories but unable to stave off his end.

Polish authorities did not look kindly on Has’s film. Despite being Poland’s most expensive production ever at the time of its making, The Hourglass Sanatorium was suppressed; its represented ruin held to be a comment on the poor condition of many of Poland’s institutions and manors. Perhaps more significantly, Has, the son of a Jewish father and Catholic mother, had significantly elaborated upon the Jewish aspects of Bruno Schulz’s source material (including imagery of pogroms and allusions to the Holocaust), a bold statement following an anti-Semitic campaign by the Polish government that saw around 30,000 Polish Jews leave the country, essentially putting an end to Jewish culture within the nation. The film was smuggled out of Poland to the 1973 Cannes Film Festival where Ingrid Bergman’s jury honoured The Hourglass Sanatorium with the Jury Prize, but Polish authorities did not soften their attitude toward Has and it would be a decade before another film by the director would be released.

The Hourglass Sanatorium‘s carnivalesque rumination on sex, death, youth, and memory, all within the character of a specific time and place (in this case, turn-of-the-century Galicia), gives the film a sensibility akin to Fellini, particularly his fanciful colour films. Has denies us a clear, linear narrative, and instead offers a film that seems to orbit an uncertain premise, passing through various contextual constellations, often more than once, but only glimpsing at its gravitational centre. Józef wanders, often childlike, from one memory/dreamscape to another (Has built adjoining sets to allow for these seamless transitions), but is distracted by his circling and his misapprehended quest for insight to notice his own mortality rooting his travels. In this way, these orbits are decaying in every sense of the expression. The pull of Józef’s approaching death, or his undeath, impedes his imaginative voyage. His fantasies increasingly betray him, as Bianca chooses Rudolph over him and his father denies him the complete knowledge he aspires for. Rot creeps into Józef dreamworld, whether it be the decrepit condition of his father’s fabrics or his own physical deterioration as he begins to assume the role of the train conductor, the film’s death figure. Time in The Hourglass Sanatorium may be circular and/or infinite, but Józef’s capacity to occupy it, let alone control it or exhaust it, is severely limited and all things, be they people, places, or cultures, all come to their modest, grasping ends.

Many discussions of The Hourglass Sanatorium struggle with the problem of its adaptation. Has adapts the film from a dozen different stories by Bruno Schulz, a Polish Jew who wrote only two collections of short stories (The Street of Crocodiles (aka Cinnamon Shops) and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass) before being shot down by a Gestapo officer in 1942 for venturing outside of his Jewish ghetto and into an “Aryan” quarter. Schulz’s stories are loaded with elaborately sensual, almost magical, descriptions that seemingly defy adaptation to film. His stories usually employ first person narration and share characters, although Has disassembles these stories, rearranging dialogue to come from different characters in alternate situations. The bulk of The Hourglass Sanatorium is derived from two stories, “Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass” and “Spring,” however Has also draws heavily from his memories of a pre-WWII Poland and its Jewish culture, as well as its punishment under the heel of the Nazis. Has’s significant intervention into Schulz’s work often leaves many discussions of the film struggling to describe the process of adaptation at work in The Hourglass Sanatorium. There is, however, an appropriate term for Has’s efforts although it is rarely employed to describe content such as this. The Hourglass Sanatorium is a work of “remix.” That’s a term that’s usually associated with hip hop and electronic music and thought of as a youthful and contemporary mode, although remix is essentially a product made through a specific methodological ethic to dismantle, rearrange, and combine to create a new work. Has’s mixing of Schulz’s stories, his reassignment of characters’ dialogue, his placement of non-contiguous environments alongside each other through editing and set design, his incorporated content from his own recollections of Polish history and culture, even his decision to have Jan Nowicki continue to play Józef even when the character is situated as a child or a young man in a given scene, demonstrate a filmmaker inspired by the source material, but not beheld to it. Has reconstructs his version of Schulz’s stories to suit his own aesthetic and political principles, merging disparate components from within and without to produce a film that is something other than adaptation and even embraces the contradictions embedded within its new arrangement.

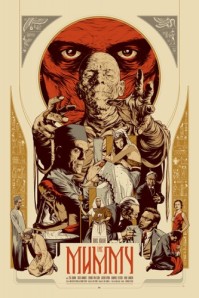

The Criterion Collection has surprisingly few examples of Polish cinema, being limited only to its edition of Knife in the Water (Roman Polanski, 1962) and its Andrzej Wajda: Three War Films box set. We can only hope that Scorsese’s touring program of Polish films promises some welcome additions to the Collection and Has’s unlimited imagination and magical approach makes him a fitting counterpoint to Criterion’s current Polish offerings. With its multitude of characters, abundance of colour, and its varied costumes and sets, a cover treatment would need to pull together a lot of elements to fully demonstrate what The Hourglass Sanatorium has to offer. Obviously up to the task is Mondo favourite Martin Ansin. Ansin’s theatrical posters employ multi-character collages and shows a talent for portraiture and expression. His work is notable for its limited colour palettes and his blocky layouts achieved by clear and inventive panels and contrasting sections of colour. Could Ansin manage to incorporate into a single one-sheet Józef with his antiquated fireman’s helmet and book of advertisements, Rudolph and his stamp book, the virtuous Bianca, the lusty Adela, Józef’s free-spirited father, the hospital’s sexually secretive doctor and nurse, the fanciful bird market, the collection of human automata, the ghostly train and its deathly conductor, the orthodox Jewish neighbourhood, and the troop of soldiers that arrest Józef for seditious dreaming? It’s a tall order, but we’d love to see the attempt.

The Criterion Collection has surprisingly few examples of Polish cinema, being limited only to its edition of Knife in the Water (Roman Polanski, 1962) and its Andrzej Wajda: Three War Films box set. We can only hope that Scorsese’s touring program of Polish films promises some welcome additions to the Collection and Has’s unlimited imagination and magical approach makes him a fitting counterpoint to Criterion’s current Polish offerings. With its multitude of characters, abundance of colour, and its varied costumes and sets, a cover treatment would need to pull together a lot of elements to fully demonstrate what The Hourglass Sanatorium has to offer. Obviously up to the task is Mondo favourite Martin Ansin. Ansin’s theatrical posters employ multi-character collages and shows a talent for portraiture and expression. His work is notable for its limited colour palettes and his blocky layouts achieved by clear and inventive panels and contrasting sections of colour. Could Ansin manage to incorporate into a single one-sheet Józef with his antiquated fireman’s helmet and book of advertisements, Rudolph and his stamp book, the virtuous Bianca, the lusty Adela, Józef’s free-spirited father, the hospital’s sexually secretive doctor and nurse, the fanciful bird market, the collection of human automata, the ghostly train and its deathly conductor, the orthodox Jewish neighbourhood, and the troop of soldiers that arrest Józef for seditious dreaming? It’s a tall order, but we’d love to see the attempt.

Credits: Nearly all discussion of The Hourglass Sanatorium makes some reference to Steve Mobia’s online analysis of the film and this is no exception. Mobia’s work is essential reading, providing a lot of insight to the film and to Schulz’s source material. A debt is also owed to David Melville’s essay “‘The Fiery Beauty of the World’: Wojciech Has and The Hourglass Sanatorium“ at Senses of Cinema. The Scorsese introduction was a natural choice given his “Masterpieces of Polish Cinema” program presently touring. Scorsese even provides a brief introduction to the program describing the origins and motivations for organizing the series. Leonard Orr was chosen to discuss the film’s relationship to the Holocaust and to European Jewish history given his brief paper “Post-Memory and Postmodern: The Value of Teaching Experimental Holocaust Fiction” wherein he advocates moving beyond canonized survival memoirists and finding value in fictionalized approaches that includes the work of Bruno Schulz. The Borys Lankosz interview is based on Nick Hodge’s Krokow Post article. Rowena Santos Aquino has previously been a contributor to Criterion’s website and was chosen as an essay writer for her review at Next Projection. The “Masterpieces of Polish Cinema” series is distributed with the involvement of Milestone Films and so the chances of Criterion is releasing some of these titles may be less likely. On the other hand, Milestone has a relatively modest catalog and so the idea of it releasing all 21 films on hard media also seems unlikely. Truth be told, MMC! would be happy to see editions of these films from either label, as long as someone makes it happen.

Credits: Nearly all discussion of The Hourglass Sanatorium makes some reference to Steve Mobia’s online analysis of the film and this is no exception. Mobia’s work is essential reading, providing a lot of insight to the film and to Schulz’s source material. A debt is also owed to David Melville’s essay “‘The Fiery Beauty of the World’: Wojciech Has and The Hourglass Sanatorium“ at Senses of Cinema. The Scorsese introduction was a natural choice given his “Masterpieces of Polish Cinema” program presently touring. Scorsese even provides a brief introduction to the program describing the origins and motivations for organizing the series. Leonard Orr was chosen to discuss the film’s relationship to the Holocaust and to European Jewish history given his brief paper “Post-Memory and Postmodern: The Value of Teaching Experimental Holocaust Fiction” wherein he advocates moving beyond canonized survival memoirists and finding value in fictionalized approaches that includes the work of Bruno Schulz. The Borys Lankosz interview is based on Nick Hodge’s Krokow Post article. Rowena Santos Aquino has previously been a contributor to Criterion’s website and was chosen as an essay writer for her review at Next Projection. The “Masterpieces of Polish Cinema” series is distributed with the involvement of Milestone Films and so the chances of Criterion is releasing some of these titles may be less likely. On the other hand, Milestone has a relatively modest catalog and so the idea of it releasing all 21 films on hard media also seems unlikely. Truth be told, MMC! would be happy to see editions of these films from either label, as long as someone makes it happen.

Wojciech Jerzy Has is a genius, no doubts about that. His works easily rivals the very best of Jodorowsky, Fellini or Buñuel If he had been born in “The West” he would be now cherished by many. But if it happened would have he possessed that typical Polish melancholia-meets-surrealism visual instinct? .